BECOMING BIGFOOT: The Process of Writing Stories

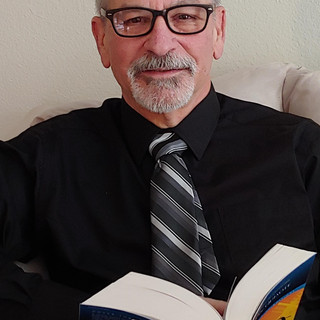

- Jack LaFountain

- Nov 8, 2020

- 8 min read

In every work of fiction the author’s integrity is at stake, and in that integrity lies the power of their words

Write what you know! Every writer has come across that nugget of writing wisdom. It’s accurate enough, and it’s sound advice—as far as it goes. However, if writers were to restrict themselves to what they know by experience, the literary world would be a boring place. As my personal life lacks the zing and flare necessary to be worthy of a memoir or a fictional thriller, I am forced to write less about what I know and more about what I imagine.

I believe a fiction writer’s job is to write what they envision, learning as they go whatever it is they need to know to fill in the holes. Imagination is not an obstacle to writing what you know. On the contrary, it means stretching that known quantity as far as you can without breaking, and all the while lying your backside off. A good lie is truth with a twist. So too is good fiction. It starts with all the truth an author can cram into the story. The strands of truth are then stretched, and he weaves a lie through the gaps. The goal is to convince the reader to swallow the lie right along with the truth, and in doing so, step into that world of make-believe (lies) that is the writer’s dream.

In March, I set out to write a book about Bigfoot. I have heard many Bigfoot stories, and for me, they all lacked one thing. Not the truth, but the ability to draw me into the story. They’re like listening to court testimony without Gregory Peck to do the questioning. This is not a criticism of the witnesses; this kind of no-frills, factual retelling is the actual intent of the person recounting their experience. Knowing that their veracity will be questioned, they must cling solely to the facts. They are not out to entertain; they only wish to tell their story and be believed. If the hearer has had an experience of their own, this testimonial style may provide enough detail for them to form a mental picture. However, the sense I get from most Bigfoot encounter stories, is an underlying desire to do more than just preach to the choir. These storytellers want everyone to believe them.

As a writer, I understand my book must both entertain and persuade. It must be factual while setting a match to the reader’s imagination. The emphasis in my case is on entertaining my audience. Chances are that those buying a book of Bigfoot stories are already believers. They are also very savvy on the subject of Sasquatch. Therein lies the challenge. How do I convince experts on the subject to read the book, buy my lie, and walk away smiling at the end?

The answer is to resort to literary devilry. I must look the reader in the eye, while pouring them a glass of water, and slip a shot of moonshine into the glass without them seeing it. A bit of writerly prestidigitation, hoping to quench their thirst while lowering their inhibitions, so they leave the book feeling like they had a good time.

I distill the moonshine in my head. It’s ready for my fingers to type into the story, pouring it into the cool, clear water of the truth. I have found that for a group of people trying to convince the world of the same truth, Squatchers are a contrary group. No offense. These are my people, but they eat one another for lunch. It reminds me of my years as a preacher. So, this truth I am telling had better be good, or the lie is never going to fly. For that truth to be cool and clear doesn’t hurt anything either.

The basis for the Bigfoot stories in my forthcoming book, Tracks, is to present credible accounts of genuine encounters, perhaps seasoned with some native myth. Myth, in the usual understanding of the word, means an unfounded or false notion. However, it also means a traditional story that, to all outward appearances, relates to historical events and serves to explain a practice, belief, or natural phenomenon. That is how I use the word. There are better words for the other meaning.

I set these stories in actual places that are geographically correct to the best of my knowledge; most are places I have lived in or visited. They are then dropped into the world in authentic time periods and presented with historical accuracy. If there is a full moon in the story, there better have really been a full moon on the night of the actual incident.

But what about those writers who say, Nobody will notice any inaccuracies? They might even be correct in their assumption. I don’t think so, but I will give them the benefit of the doubt. For my money, in every work of fiction the author’s integrity is at stake, and in that integrity lies the power of their words. I will lie to the reader eventually, but when I do, they will agree to it because they want the rush of that moonshine.

The third of the four stories in my book presented a tough challenge with what writers call point of view, or POV. It has to do with whose “eyes” we are seeing the story through. In a short story like this one, it’s best to stick to a single point of view. So, in this tale, we see the story through the eyes of Bigfoot himself. With most characters, the writer can put on the protagonist’s shoes and walk around in them to get a feel for how that person thinks and acts in any given situation.

That is extremely difficult, even under the best of circumstances, when the writer steps outside of what he knows. I have written stories with female protagonists, for example. I have a few clues about how women behave and the kind of things they often say. But I don’t have a single sound idea about how women think or feel. When I write a female character, I ask a woman to review my work for soundness. I trust my editor, who happens to be a woman, to call me out if that tactic fails. Male or female, no two persons of either gender think alike, so there is some wiggle room, but not much.

Here’s the unique difficulty with this particular story. Under normal circumstances every point of view character is a person. As unique as we like to think ourselves, people are not that different. How many times have you watched a movie and shouted at the idiot on the screen, “Don’t just stand there, shoot him! Shoot him!” We do that because we think like a person and expect the same from the character.

In this case, the character is not a person. It’s a hairy, bipedal hominid that some people don’t believe even exists. So how do you get in those shoes...er...big feet? How does the writer become Bigfoot? To tell this story with an authoritative, believable voice, this is exactly what I had to do.

When I sat down to write Tracks, I had just published a book called Bayou Moon, in which one of the principal characters was a rougarou...a kind of Cajun-spiced werewolf. So, I started into the first chapter of this Bigfoot story with a false confidence. It immediately became clear that I dodged that issue of point of view entirely with my rougarou. Besides the fact that I had not used the rougarou’s point of view anywhere in that story, my editor reminded me of a conversation in Bayou Moon that went like this:

“You’re not going to catch this rougarou,” Johnny began. “Not by chasing after him. You’re going to have to get in front of him. Yes, dis rougarou, he thinks… you got to out-think him.”

“If only I thought like a rougarou instead of a man,” Landry told him.

“Sheriff, now you make me sad.”

“What?”

“Dis here rougarou is a man,” Johnny said. “I thought you knew dat. Don’t dat gut of yours talk to you?”

My rougarou not only thought like a man, under all that hair, he was a man. My Bigfoot could not be like that… could he?

To deal with approaching the POV of a Bigfoot, I did what I usually do in such cases; I turned to the audience, the potential readers. And from them, I received lots of opinions. Opinions are like...well, they are common, and everybody has one. One witness told me, “You can see the intelligence in their eyes.” I believe him, he’s obviously been closer than I have. However, I see intelligence in my dog’s eyes. Is Bigfoot only as intelligent as a dog, and how would that look from the inside? How was I to know?

It seems most of what believers took for signs of intelligent reasoning by Bigfoot could either have another explanation, or else they shed no genuine light on what I feel constitutes reasoned action. I would either have to abandon the storyline… or dig deeper for an answer. I persisted because I am convinced there is a degree of reason working in these creatures. That could be a personal prejudice, but I wasn’t ready to give up the supposition.

The answer, I believed, lay in the creature’s known actions. Remember, I wanted truth wherever possible. I thought there had to be documented actions out there that showed a measure of intelligence beyond instinct and mimicry. If there wasn’t, I had no story.

A little intelligent reasoning on my part turned on the bulb. The first light to come on was something I already knew about but had overlooked. Some people who had extended encounters with these creatures have reported communication between them that sounded like language.

Language, or more precisely, speech is really nothing more than thinking out loud. True, many animals communicate, and we identify calls, howls, whistles...etc. But these stories of Bigfoot encounters weren’t reports of calls, but speech, recognized as such by people who were themselves multilingual. Still, I wanted more proof. The witnesses could have been mistaken or scared, or maybe built memory after the fact.

I found a second story. This was one of Sasquatch learning to recognize the consequences of their actions. Wow, I know people who can’t do that! These Sasquatches, by experimentation, learned that their presence set off motion-activated lights. They not only determined that their presence turned on the lights, but they measured the range of the detectors and set out sticks to mark the boundary. That is cause-and-effect thinking with a preventative solution. It’s simple, but reasoned. Bigfoot thinks.

All good, right? No. My brilliant deduction of language created another universe of problems. What does a Sasquatch call a house, a human, a cow? Yeah, what about that, ghost buster? Here, there was no way to know. There’s no Bigfoot-to-English dictionary. And no reason to assume they speak English. Tarzan spoke French when Jane found him—though he never did in the movies.

The first story in Tracks takes place around the Hood Canal in Washington. The Salish people there told stories about a Bigfoot being. Theirs, the Seeahtik, could speak every native dialect in the area. But this did not provide me with a way around the problem for the third story. I had no such indigenous account in this instance, and it would be a cheat to assume one. Though I admit I do have a friendly native-and-Bigfoot connection in the third story, it is not a linguistic one.

In any case, I was not prepared to invent an entire language as Tolkien did for his elves. I’m ambitious, but not that ambitious… even were I already certain that this would not be my last foray into Bigfoot storytelling. My solution? A multilevel approach, incorporating childlike naming, mimicry, transliteration, and gesturing. As I neared completion of the story, I learned that the black crested macaque of Indonesia, in an astonishing feat of communications, can interpret facial expressions to assess the likely outcome of an encounter.

We may not know what this handsome fellow is thinking, but his friends do. Not only do these monkeys know the potential outcome of a meeting, they seem to know how to adapt their approach to make that outcome better. Which is something I wish we humans could master.

As a writer, personal integrity, and as much truth as I can gather, are what I promise to my readers from every story. I do so hoping that, in the final analysis, separating my facts from my fantasy will not only be difficult, but will be something the reader doesn’t even think about on their journey through my head.

Comments